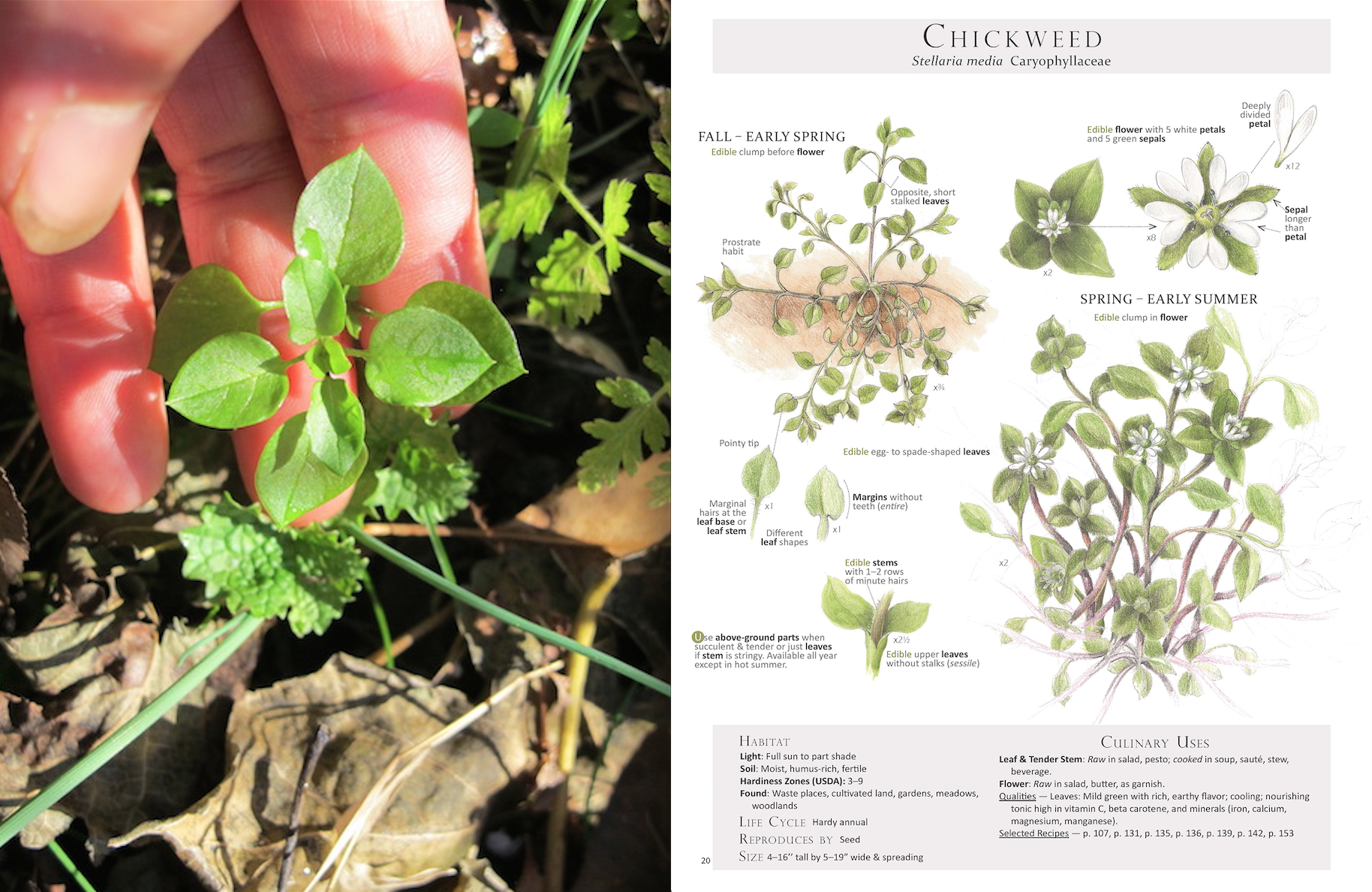

Wild salads are back in full swing! Here in the Northeastern U.S., autumn brings rain and cooler weather that encourages tender, new plant growth which means tasty salads. I always think of wild salads as a celebration of time and place and these are the days to celebrate: chickweed, purple dead nettle, star chickweed, violet, wild lettuce, garlic mustard, ox eye daisy, sheep sorrel, mallow and more.

Raw and dressed wild plants offer incredible flavor, and are full of therapeutic essential oils, vitamin C, and other nutrients undiminished by cooking. Eaten right after picking, wild salads fill the body and spirit with vigorous, feral life force. After eating one, I often experience a wider sense of perception while feeling simultaneously more awake and relaxed. When I take beginners on edible-plant walks I usually bring a bowl and simple vinaigrette dressing. While we are out in the field exploring the plants, we gather them into the bowl, toss them with the vinaigrette and complete the educational process by chewing and savoring them. Consistently, wild salads convert inexperienced foragers to regular enthusiasts. Hundreds of wild salads later, they find the salads just as delicious.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Wild Salad practice: I encourage students to make wild salads every day of the growing season as a meditative practice that connects us to nature, strengthens our plant-identification skills, and nourishes us with tasty, healthy salads.

Common mallow (Malva neglecta)

Common mallow illustration from Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook.

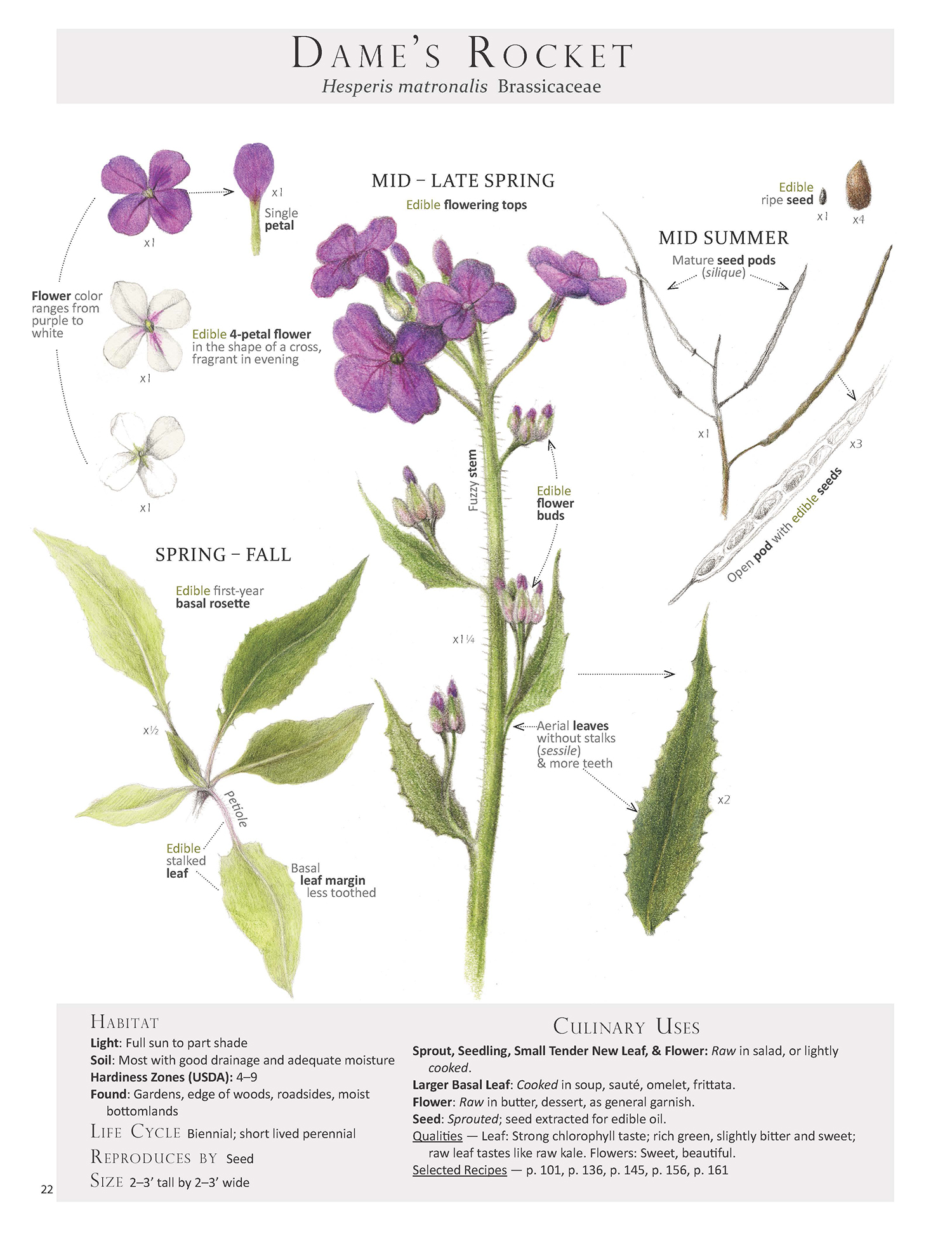

Dame's Rocket (Hesperis Matronalis) in basal rosette. Harvesting new tender, inner leaves for today's salad.

Dame's Rocket illustration from Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook.

Wild Salad-Making Technique

Today's wild salad, just picked and ready for dressing. Contains: chickweed, purple dead nettle, sweet cicely, star chickweed, violet, mallow, garlic mustard, ox eye daisy, and sheep sorrel.

Assembling a wild salad is as easy as throwing any wild edibles — that can be eaten raw — into a bowl. And yet to insure a tasty experience I suggest you consider the following:

When to Harvest Plants for Salad

Make sure to harvest plant parts when they are vibrant and perky, not wilted or dull. This usually means gathering plants before or after the heat of the sun has passed. If you must pick them during the hottest and most droopy part of the day, eat them right away or soak them in cold water to crisp them up.

The best stage to gather wild plant parts for salad is when they are young, tender and succulent. Keep in mind that young and tender parts can be harvested from a mature plant. You can harvest tender leaves from a mature lamb’s quarter plant throughout most of its life. Additionally flowers for salads are usually picked from older plants.

Cleaning Plants

To ready the plants for the salad bowl, shake and gently slap the plants before picking them to knock off any bugs or debris. If you want to further clean the plants, place them in a large bowl of cold water, gently swirl them around, and soak them for a few minutes. Repeat if needed. Then place plants in a salad spinner and spin to remove all the water. Removing the moisture allows the salad dressing to adhere to the plants. If not using right away place plants in a sealed plastic bag or container and store in the refrigerator.

Tearing the Plants into Bite-Size Pieces

Since wild plants tend to be tougher than cultivated ones, tearing them into bite size pieces makes wild salads easier to chew. These bite-size pieces mix easily when tossed, dispersing the plant flavors. I prefer to gently tear, rather than cut, large leaves and flowers into bite-size or smaller pieces, trying not to bruise them in the process. This handwork takes time, but slowing down to touch and smell the ingredients helps us appreciate what we are about to eat. Gentle cutting with a knife or scissor is also acceptable. When small enough, whole leaves and flowers can be added to the salad. Some very strongly flavored plants are best torn into very small pieces or minced, as directed in specific salads.

Dressing and Tossing the Salad

All salads, but especially wild ones, deserve a good dressing. Good refers to quantity as well as quality of dressing. For a single serving, I suggest using at least 2–3 tablespoons of dressing per 2 large handfuls of salad. The dressing should be made of the highest quality ingredients and can be a simple vinaigrette or a more elaborate combination. Please see Salad Dressings in Foraging & Feasting for some excellent choices. Once the salad has been torn and placed in a bowl, dribble the dressing around the plants and toss them well for 30 seconds or so, making sure to thoroughly coat all the plant material. Let the salad sit for 1–2 minutes before serving to allow the dressing to penetrate the plants. This way of preparing wild salads makes them more delicious and more digestible.

Violet (Viola sororia). Note gill-over-the-ground (Glechoma hederacea), considered a violet look alike, grows in the background. FYI, gill is also edible as a culinary garnish and medicine.

A large portion of this text and the botanical illustrations appear in Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook by (me) Dina Falconi; illustrated by Wendy Hollender.